The Daily Texan: FALUN GONG IMPRISONMENTS claim UT student's father

Unity Petersen/Daily Texan Staff

Volume 102, No. 2 Wednesday, September 5, 2001

á

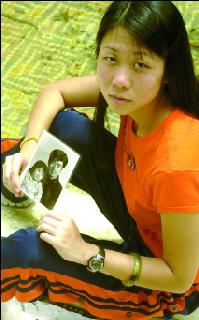

Danielle Wang, a civil engineering sophomore, holds a photograph of her father, who has been imprisoned in China since 1999 for practicing the ancient meditative exercises of Falun Dafa. The practice was banned by Chinese President Jiang Zemin on July 20, 1999.

á

It has been more than two years since the Chinese government arrested Danielle Wang's father. Today, unsure about her father's whereabouts, Wang, a civil engineering sophomore, clings to hope that she will someday see him again.

Ever since her father's July 20, 1999 arrest, Wang has made it her mission to seek freedom for her father and other Falun Dafa practitioners detained in China. Wang's father was arrested for being one of the primary contact people for Falun Gong, a practice in which mind and body exercises are used to cleanse and heal, also known as Falun Dafa.

The Chinese government banned the practice in July 1999, saying it was not registered as a social organization, thus making it illegal. Since then, many Chinese citizens and human rights organizations have accused the Chinese government of severely torturing or murdering practitioners.

"When I moved to the United States three years ago, I never would have thought that that would be the last time I would see my father," said Wang, who was born in China.

Wang has spent this summer touring the country, giving press conferences and becoming an ardent voice for the imprisoned practitioners. On Sept. 12, following a rally for Falun Gong victims on the West Mall, she will observe a 24-hour hunger strike in honor of those persecuted.

"We go 24 hours without food or water to symbolize what Falun Gong victims in China are going through," Wang said. "We would go on strike longer, but since we are students we don't have the time."

Wang's parents divorced when she was 10, and her mother moved to the United States. But Wang stayed in China with her father until she was 18, then moved to San Antonio to attend an American high school. Being raised mostly by her father, she also became a devoted Falun Gong practitioner.

"I have been practicing for 10 years because it's very healthy, gentle and peaceful," she said. "It teaches you to be a better person."

Just a year after Wang moved to the United States, in April 1999, the Chinese government began speaking out against Falun Gong. It was then that Wang's father, Zhiwen Wang, a railroad engineer, started working to preserve practitioners' rights in the country. He joined others in appealing to newspapers and local governments, but when those efforts failed, they traveled to rally in Beijing, where most high-ranking Chinese officials work.

Wang said her father was one of four advocates chosen to speak to the prime minister at the Beijing rally. Following that meeting, she said, his telephone was monitored, and he was often followed.

"When I called my father I could hear these beeps when we spoke," she said. "I knew our calls were being monitored. He knew he was being watched."

Living on the other side of the world, Wang worried about her father's safety, but she said he never seemed fearful because he strongly believed in the principles of Falun Gong.

"He would say, 'I didn't do anything wrong. I won't hide because I didn't do anything that was wrong,'" she said.

She said he never condemned the government, but wished that they would become more accepting of the practice.

After the arrest, Chinese officials told her aunt, who lives in China, that Zhiwen Wang would have a court hearing in December. On Christmas Eve 1999,

Wang saw her father on CNN, escorted into the proceeding wearing only an oversized police jacket, with his hair faded from black to gray and with several missing teeth.

"I could not believe that this was my father," Wang said. "I had never seen that look on his face before. He looked so beaten up. It was so hurtful."

He was sentenced to 16 years for leading the Falun Gong rally.

It was that image of her father that steered Wang into a depressive state that caused her to neglect everything, except the idea of traveling back to China to help him. She stopped eating regularly and spent hours sobbing, imagining what her father was going though.

"I was so close to my father that I just acted crazy," she said. "I just wanted to get back to China to find him. Then, I realized, I had to do something to help the victims of Falun Gong, because if we don't stand up, there will be no voice."

She stayed in touch with him through letters, but said that she knew the prison guards read their correspondence. Her aunt visited her father regularly and told Danielle Wang of his condition and spirits. Throughout his imprisonment, he remained faithful to the practices of the Falun Gong, she said.

But six months ago, her father was transferred to another prison, and neither she nor her aunt have heard from him since. She said she fears the worst, but tries to remain optimistic.

In addition to traveling to seven states this summer for press conferences about the victims and contacting politicians, she and fellow activist Joy Zhou, a graduate student, founded the Falun Dafa Students Association last year, but participation is scant at about two active members.

"People don't know what Falun Gong is so they don't want to get involved," she said. "I want to clear its name."

Zhou met Wang last year on campus, and the two quickly became good friends after learning that they both practiced Falun Gong. But despite facing similiar struggles in China, Zhou said Wang keeps her pain private even from her.

"Sometimes she misses her father very much, but she doesn't let me know and suffer with her," Zhou said. "At the beginning of this year, I invited her to have dumplings at my house, and when she saw my son play with my husband, she said softly, 'I miss my father. When I was a little girl my father played with me like this.' At that moment I wanted to cry. She always has a smiling face, but that's not what she feels in her heart."

She has also had support from other local practitioners, many who commend her strength and determination.

"I really admire her," said William Cheung, an Austin resident and Falun Gong practitioner who is friends with Wang. "I mean you grow up in a country that struggles with human rights, but you don't ever expect that it will go so far that your father will be imprisoned for doing nothing wrong. Under the circumstances, she has no hatred for the Chinese government; she just wants her father released. That really inspires me."

Wang said she believes the Chinese government is now watching her, as she said she has been blocked from entering certain Falun Gong Web sites.

"I have been on the Internet and suddenly get disconnected when I get to a Falun Gong site, or I'll be denied access to a site," she said.

She knows that if she were to return to China, she would face arrest. She no longer considers going back an option. Instead, she is hoping to improve the lives of the Falun Gong victims in China through her efforts in the United States. When she speaks of her own mission, she echoes the words of her father.

"I am not scared because I think what I'm doing is right," she said.

http://www.dailytexanonline.com/09-05-01/01090508_s01_Falun.html

á