Canberra's bumbling in its handling of Chinese diplomatic defector Chen

Yonglin is a direct result of a lack of clarity, realism and forthrightness in

the Federal Government's China policy.

Canberra's bumbling in its handling of Chinese diplomatic defector Chen

Yonglin is a direct result of a lack of clarity, realism and forthrightness in

the Federal Government's China policy.

Prime Minister John Howard recognises, correctly, that China will be vitally important to Australia over the next half century, and has, rightly, done all he can to assiduously cultivate good relations with that country.

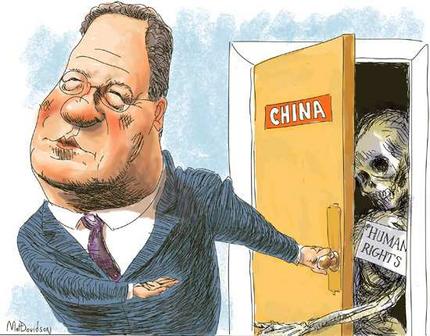

But the Government has naively thought it possible to dodge having to deal with the more unsavoury nature of what, despite some progress on human rights, is still a politically repressive regime.

In pursuing the relationship, the Government has put its head in the sand about the nastier side of China - and hoped the community would too.

Then out pops Chen, appealing for political asylum and highlighting China's dark side.

It is a side Chen claims to know a good deal about. He says his job at the consulate in Sydney focused on monitoring the activities of Falun Gong and other dissident groups in Australia. His May 25 letter to the Immigration Department seeking political asylum said: "My spirit is severely distressed for my sin of working for the unjustified authority in somewhat evil way, and my hair turns white quickly in the last four years for frequent nightmares."

[...]

His appeal threw the Government into a funk. It could only be bad news, just when the bilateral relationship had a new glow, with Howard's successful visit to China and the go-ahead for negotiations on an Australia-China free trade agreement.

It is unsurprising and quite reasonable that Foreign Minister Alexander Downer rejected Chen being given platinum membership in the asylum club - what is known as "territorial" asylum.

Does anyone think that, after all this, Chen will be, or could be, sent back to China?"

That went, famously, to Vladimir Petrov, and also to a Ukrainian 18-year-old in a red bikini who, in 1979, swam ashore from a Russian cruise ship in Sydney Harbour.

Territorial asylum was closely associated with the Cold War. Reserved for the most serious cases, it is also a foreign policy statement - a declaration that a person has come from an unfriendly country. This, obviously, is not the situation with Chen. A territorial visa was unnecessary and would have been provocative to the Chinese.

It is not this refusal that is the problem; rather, it is the Government's failure to properly and expeditiously give Chen appropriate protection. It dithered, delayed and, when the affair broke open publicly, dissembled.

Chen was quickly told he wouldn't get territorial asylum and must apply for some other sort of visa if he really wanted to stay. Then there was a hiatus. Downer and Foreign Affairs hoped the whole thing would go away - by Chen going away. For once, Immigration isn't the villain. In Parliament this week, the Government will be pushed on what Downer and his department said and did, and on contacts, including by Immigration, with China's embassy and consulate.

Eventually, an alarmed and desperate Chen went public last weekend. The Government was caught in the spotlight, looking flustered. Downer and Immigration Minister Amanda Vanstone contradicted one another over what had happened. Downer argued there had been no application for political asylum. This relied on the arcane point that you can't actually apply - the minister has to take the initiative. The Government tried to make Chen sound like anyone else seeking a protection visa.

But, obviously, Chen is different from the 1000 or so Chinese who annually apply while in Australia to stay here. (In 2003-04, 77 were granted protection visas. The Chinese mostly come on regular visas and then apply. There is not a high rate of overstayers among Chinese.) As a diplomat, Chen is automatically special. The Government should have been upfront about that, and dealt with his status at once.

It is nonsense that his case is still being processed. The processing must either be a farce or a disaster: a farce if it is assumed this is just going through the motions, a disaster if he was told to return. Does anyone think that, after all this, Chen will be, or could be, sent back to China? Hardly. Tony Abbott and Peter Costello said as much during the week. "He is at no risk of being sent back to China," Abbot said. If there was any doubt when Chen approached the Government, there can't be after his public statements since. So why not finalise his case at once?

Chen's claim had a ripple effect. It flushed out Hao Fengjun, a former officer with the 610 security bureau, who, in Australia on a tourist visa earlier this year, applied for protection. Then came news of an unnamed former state security official, witness to a man being beaten to death in China, who has already been granted refugee status.

Hao detailed persecution of dissidents in China. He also said he backed Chen's claim of large numbers of informants in Australia, and told how the activities of Falun Gong adherents here are reported back to China. This was a further glimpse of a side of China that the Chinese don't want exposed and the Australian Government would prefer not to have to confront.

ASIO will examine whatever information Chen and Hao have, although there is no great sense of excitement about it. It is not expected to relate to the high end of Chinese espionage in Australia, and, in that sense, it is not so much about "spying" on Australian secrets (strategic or economic) as about Chinese pursuing other Chinese (which, while not acceptable, is just not as interesting to our intelligence bods).

It is well known that the Chinese watch and harass in Australia those associated with Falun Gong and other dissident groups.

In recent years, Australian authorities have warned Chinese officialdom several times about overstepping the mark.

Both the Australian and Chinese Governments have a strong interest in preventing the Chen affair putting a serious dent in relations between the two countries.

Getting Chen's future settled fast would help.

But that still leaves the issue of how the Government responds on the wider matter of China's abuses of human rights.

These are documented in a recent Amnesty International report covering 2004. It said that there was progress towards reform in some areas, "but this failed to have a significant impact on serious and widespread human rights' violations perpetrated across the country.

"Tens of thousands of people continued to be detained or imprisoned in violation of their fundamental human rights and were at high risk of torture or ill-treatment.

"Thousands of people" the report said, "were sentenced to death or executed, many after unfair trials."

What is being highlighted in the political flow-on from the Chen affair is the weakness of the Australian Government's stance on human rights in China.

Not that the public has seemed too worried. Apart from the Greens' Bob Brown, there hasn't been the same agitation in Australia as in the US, where activists on both left and right have been vocal about Chinese behaviour.

Falun Gong plaintiffs are now challenging in the ACT Supreme Court the orders Downer signs that authorise police to stop its members holding banners and making a noise outside the Chinese embassy.

Downer has done this since 2002, under an international convention that protects the dignity of diplomatic missions.

Imagine if protesters could be stopped from holding banners outside the Lodge or Parliament.

In 2003, after Bob Brown and his Greens' colleague Kerry Nettle interrupted President George Bush's address to the Australian Parliament, the two senators were banned from the following day's parliamentary sitting that heard President Hu Jintao. The Chinese had threatened that their President would not speak if there was danger of an incident.

A few years ago, Australia used to co-sponsor a resolution at the United Nations Human Rights Commission. It replaced this with a dialogue with China on human rights. The net result has been to play down the issue.

In a May 2004 submission to a parliamentary inquiry into Australia's human rights dialogue process, academic Ann Kent, from the Australian National University's law faculty and a specialist on human rights in China, argued that the dialogue was neither transparent nor effective.

She said China made it a precondition of the talks that Australia didn't co-sponsor resolutions and Australia insisted the dialogue shouldn't disturb bilateral ties.

"The result of these preconditions is that, every year, Australia approaches the bilateral dialogue with its hands already tied behind its back," she wrote. "It has no bargaining power: it is able neither to invoke the possibility of international disapproval nor to apply sufficient Australian pressure for fear of destabilising the relationship."

Kent volunteered the submission but was not, despite her expertise, invited to give evidence.

It's no good the Government pretending, to itself or China, that the China relationship can be all-round easy. Yes, we should do everything possible to achieve close economic ties.

But we should not let that compromise our voice as a liberal democracy that holds, and, when appropriate, asserts, important human rights values.

Category: Falun Dafa in the Media